With a university background in mathematics and operational research and having worked in railways in Britain, followed by a stint in telecoms consultancy, Martin Haigh started his job at oil and gas multinational Shell some twenty years ago. For eighteen years now, he has been shaping and overseeing the modelling of the scenarios at Shell. “When I came in, the feeling was that the scenarios team needed to step up, because other teams were getting better and better at doing quantified energy outlooks. The goal was to develop a more comprehensive energy system modelling capability. The Scenarios team built two principal versions of the World Energy Model in-house. Since 2017, ORTEC have been working alongside the Scenarios Team in a steadily deeper collaboration to support the modelling work. The ORTEC team have played a core role in rebuilding our latest – third – World Energy Model in a Python framework.”

"There are different ways of representing uncertainties concerning the future."

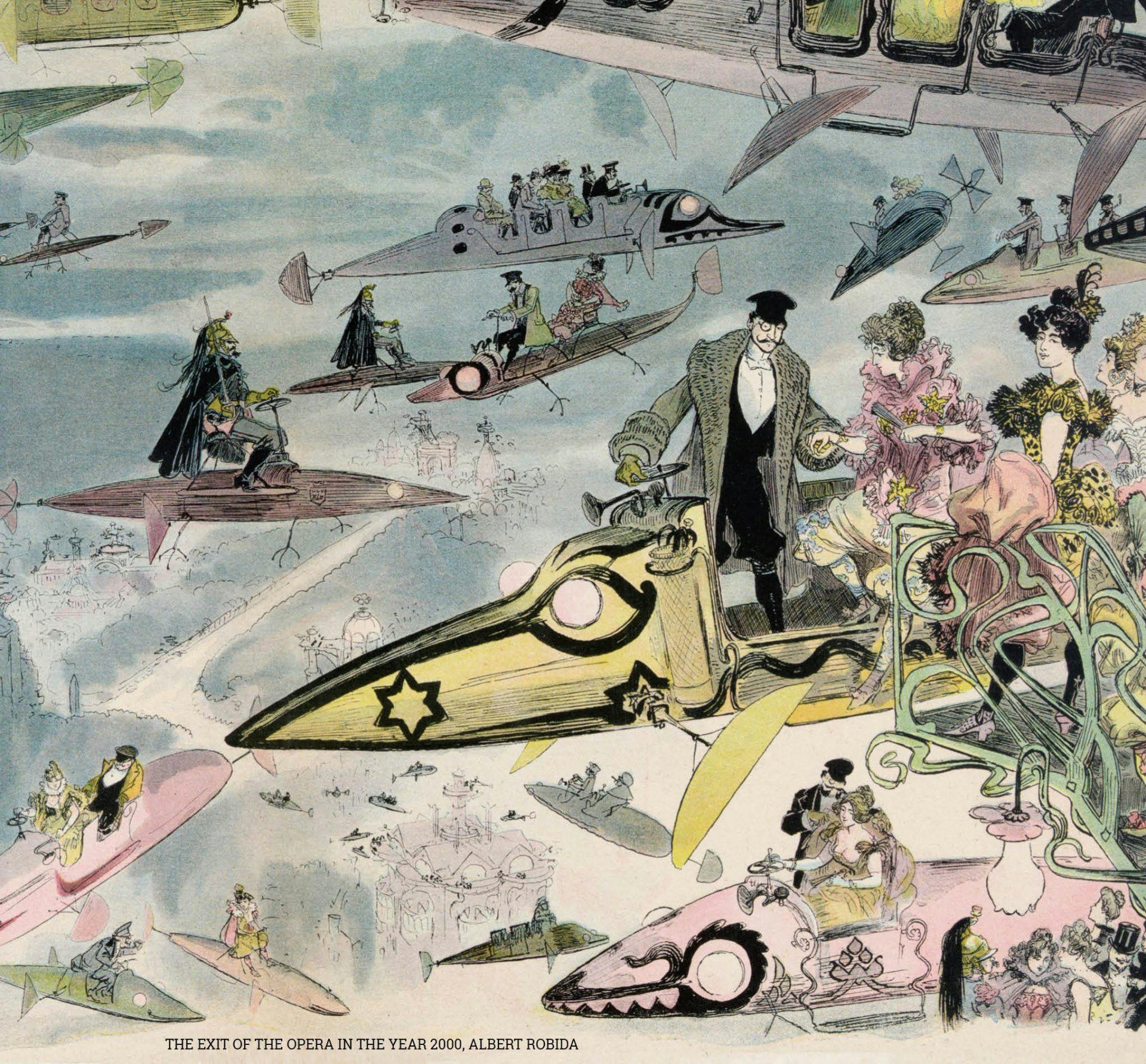

The exit of the opera

When asked what scenarios mean in Shell’s world, Haigh responds: “Our answer is that scenarios are alternative futures. But there are different ways of representing uncertainties concerning the future. A typical one, specifically if you come from a mathematical background, is to produce a forecast and an uncertainty range around that. Simulation exercises can often produce this sort of outlook. But what if the uncertainty is more structural than that? The models include certain rules about the way the world works, and that can give you a narrow range of the uncertainty. Another popular approach is what we call the normative scenario, which works back from a target that you want to achieve, to see what plan is needed to deliver that particular outcome.”

However, states Haigh, these models can be limited in capturing turning points that significantly change the trajectory of events. So, Shell uses scenarios to incorporate both qualitative and quantitative elements within a broader framework. The aim is to understand and project different outcomes based on varying unpredictable drivers, ensuring each scenario remains internally consistent. This approach is useful for stimulating discussions and understanding different perspectives on possible futures. The energy industry, due to its long-time horizons and numerous interactions with other systems, seems particularly suited for this approach. Energy scenarios touch upon politics, economics, technology, and human behavior. “We tend to overemphasize the impact of technology on our lives. To illustrate this, I often show a picture made by the French artist Albert Robida: ‘The exit of the opera in the year 2000’. He created that around 1890, and it’s the earliest image I’ve seen that has flying cars in it. Flying cars have become our image of the future since then. And here we are, 140 years later, and we still don’t have them. This shows the danger of over-emphasizing technology. In the same painting, the people supposedly leaving the opera in 2000 are wearing 19th-century clothes. Men with ruffs and women with elaborate hats. That’s a symbol of social change that tells us what is completely overlooked. And sometimes it's these social changes that we might not be looking at but that could have more impact on energy. Plus, some things do not change. That is also reflected in the picture: the bridges over the river Seine are much the same today in Paris as they were in the 19th century. There will be prints of the present into the future as well.”

"This picture illustrates the challenges with creating an accurate view of the future", as Haigh explains.

More extensive consultations

So, how does Shell ‘predict’ the future? “Well, we wouldn’t pretend to ‘predict’ the future. Rather, it’s about finding what you can say usefully about the future. When I was brought into the team, one of the challenges was the fact that the energy system is transitioning. How do you model the energy system through a transition? That raises a debate about what lessons from the past we can rely on. In statistical terms, what relationships would persist, what parameters could you even rely on, and what is up for change? In my opinion, we needed to keep more input exogenous to the model.” Haigh describes Shell’s energy modelling system as something more than ‘a giant adding machine’. “There's significant mathematical work within it. But it combines exogenous inputs and produces the cumulative result of our assumptions. Essentially, it's our way to mirror a scenario story that the team come up with, and then test its consistency and plausibility.

Last year, while we were developing the Energy Security Scenarios, we began with a series of monthly team workshops.” The sessions aimed to provide clarity on the team’s path, leading to the quantification of their understanding. “It became the most iterative process that we have achieved so far, where the preliminary numbers were scrutinized, refined, and then reshaped either to align better with the scenario narrative, or help the Scenarios Team fill out details of the narrative. Our new system has made the process far more efficient, allowing for more extensive consultations. This is crucial as stakeholders need time to digest the information, and we benefit greatly from multiple perspectives that help stress-test our models. One of the things I was a bit skeptical about to start with, was whether our new programming framework in Python would be any easier to enhance and extend to more processes than before. I wanted to extend the capability of the modelling, not just make the modelling faster. My initial fears proved unfounded. It's a more flexible platform and it is easier to upgrade. And the key case in point was that we were able to include direct air capture of CO2 and power-to-liquids. These technologies in the energy system are of great interest to the technological optimists, and we got them in ahead of other energy systems modelling teams.”

Numbers in context

In the future the model's functionality can be expanded further, leading to more detailed analyses and answers to newer, more complex questions. However, over-complicating things must be avoided, says Haigh. Another avenue is the potential integration of various models, ensuring consistency in the outputs. Lastly, there's a significant push towards democratizingz the data, making it more accessible both internally and externally. Previously, providing colleagues with detailed data required a labor-intensive process. “Now, thanks to our dashboard, we've been able to make all this data accessible to Shell staff. We're also keen on expanding this accessibility externally, but there are hurdles, such as licensing issues. I'd like to make more of this data available externally. I think most of us in the team see a great benefit for Shell in being a part of the conversation about the energy transition. We have to show how we think, where we've come to, the conclusions we've got to.” Transparency in all aspects is essential, says Haigh: “There's a danger that modelling becomes a black box, with people blindly accepting – or rejecting – the outcomes without questioning the assumptions behind them. We aim to use models as tools to explain the thought processes. Sometimes a model might yield a surprising result, not necessarily due to an error but because of the way variables scale and interact. That's why it can be valuable to project even up to 2100. Such long-term views can highlight trends and factors we might not immediately see, but which can inform earlier decisions. Helping to understand the story behind the numbers is also vital. While I can't dismiss the importance of the figures – given that my team produces them – it’s crucial to see these numbers in the correct context.”

"People sometimes confuse scenarios and strategy, thinking the scenarios directly reflect the company's future actions. But our scenarios depict what the world is doing. They are merely one of many inputs into our strategy."

Possible global directions

Speaking of context: by no means do scenarios represent Shell’s strategy. “We've even added a slide in our presentations distinguishing between scenarios and strategy. People sometimes confuse the two, thinking the scenarios directly reflect the organization’s future actions. But our scenarios depict what the world is doing. They provide context for the organization to understand possible global directions. While there may be big opportunities in the global context, Shell might also focus on niches where it has a distinct advantage, because given the sheer scale of the world’s energy system, niches can still be very large business opportunities indeed. Scenarios are merely one of many inputs into our strategy.” At the same time, scenarios are used in multiple ways, states Haigh: “And we're always striving to incorporate them more extensively. They serve as a unifying concept within the organization. If someone proposes a new business prospect to Shell's executive committee, tying it to our scenarios can give it context and significance. For instance, aligning a proposal with known scenarios like ‘Archipelagos’ or ‘Sky 2050’ helps the leadership understand its place in the broader scheme. Businesses need detailed scenarios to evaluate various transition options. We provide that broader backdrop and then allow businesses to delve deeper based on their needs.” Another application has been the creation of integrated clean energy hubs in key operational areas worldwide. Over the years, members of the Scenarios team collaborated with in-country teams to explore various energy transition possibilities in these regions. “Shell's leadership also refers to our scenarios in their communications. Sometimes they'll juxtapose our findings with those from other reputable organizations like the International Energy Agency (IEA). This helps in understanding where we align or differ with external views and why. For instance, we noted a difference in what we see as the plausible range for world energy demand in 2030 compared to the IEA's ‘Net Zero 2050’ scenario. Understanding such differences of view aids decision-making.”

Tight timeline for targets

Geographical diversity is another essential aspect. Scenario generation can be susceptible to group think, so we have to work hard to draw in different perspectives. “We prioritize global engagements, and technology has made this even more feasible nowadays. We've recently introduced the idea of archetypes in our scenarios. This stemmed from recognizing that the green-first philosophy of energy transition dominant in Western Europe isn't universally embraced. The goal is to trigger debate and consider multiple world views because a myriad of challenges exists, says Haigh, from climate concerns to developmental issues. While I'm proud to work for an organization that’s a part of this transitional story, a sustainable business model is crucial. In the triumvirate of consumer, government, and business, each player tends to argue the other two should be more proactive. However, I'd argue that government policy is paramount. They have the tools to coordinate, support emerging technologies, and provide various types of support, from R&D to integration into the system. Companies, too, play a vital role. Those that take the initiative and demonstrate innovation, both in business models and technology, will emerge as leaders. The major challenge, for organizations like Shell and the system at large, is scaling solutions quickly. The timeline for targets, such as net-zero by 2050, is tight. Thus, solutions need to not just be effective but also rapidly scalable.” In the end, Haigh stays optimistic: “Part of our work is to help guide discussions, drawing on sources like the IPCC. Rapid changes are indeed occurring, but we mustn't lose hope due to dystopian narratives. Humans have shown great resilience and adaptability in the past.”

1 The companies in which Shell plc directly and indirectly owns investments are separate legal entities. In this content “Shell”, “Shell Group” and “Group” are sometimes used for convenience where references are made to Shell plc and its subsidiaries in general.

About Martin Haigh

Martin is Senior Energy Adviser at Shell and leads the Energy Fundamentals team, which explores how energy demand is evolving in different countries and sectors.

Martin joined Shell in 2003 and has been a member of the Shell Scenarios team since 2004. He has led the development of Shell’s World Energy Model, which has underpinned the last five Shell scenario rounds and built on Shell’s 50-year history in scenario planning.

Martin works with many institutions, including MIT’s Climate Science team and the International Energy Agency, and has participated in the IPCC Sixth Assessment focusing on energy systems modelling. He is a Fellow of the Royal Geographic Society.

Martin has a background in mathematics. He has experience in mathematical and economic modelling in the transport, telecom and energy industries.