Data and algorithms: blessing or curse?

Read time: 5 minutesIn the title of my 1993 dissertation, I used the word “algorithm”. Few people knew the term back then, but today everyone does, and with that it seems to represent something untrustworthy: algorithms are opaque, discriminatory, and might even bring you into discredit. Just think of the Dutch childcare benefits scandal that has vilified so many innocent parents in the Netherlands. But do we really know what algorithms are?

An article by Goos Kant, Managing Partner at ORTEC and Professor of Logistics Optimization. This article is based on an article that was originally published in Nederlands Dagblad on July 18, 2022.

According to Wikipedia, an algorithm is a recipe used to solve a mathematical problem or perform a computation: it is a sequence of instructions that leads from a given initial state to a final ending state with a clear result.

A practical example: suppose you want to organize a door-to-door fundraising event. You have lots of data on historical revenues per fundraiser and city district in recent years, but now you’re short on fundraisers. You could decide to limit your fundraising efforts to those districts that produced the highest revenues in recent years. A simple algorithm will show you exactly where you need to go.

There’s a lot you can do with data and smart algorithms, but there are strings attached.

Goos Kant, Managing Partner at ORTEC and Professor of Logistics Optimization

"Few people knew the term back then, but today everyone does, and with that it seems to represent something untrustworthy: algorithms are opaque, discriminatory and might even bring you into discredit."

The bad

The police can adopt a similar approach: if they don’t have enough officers to keep the peace and enforce the law everywhere, they can choose to deploy officers to districts that have experienced a relatively large number of incidents in recent years. Right away this feels problematic. The highly biased underlying assumption is “Once a thief, always a thief”. Furthermore, the disparity between good and bad districts will only get worse if police presence is scaled back in the “good” parts of town. In other words, the police would do well to tread carefully when using algorithms this way.

Vast quantities of data are interesting. In fact, data has been called “the new oil”. However, those who have the data also have the power. Large organizations like Google and Facebook have based their entire revenue model on this assumption. The downside of using a free service is that you pay by effectively sacrificing your privacy. The services use your data to learn things about you and then sell these insights to allow for targeted advertising. Similarly, social media remember who you are and what your interests are. This is called profiling, and algorithms hand-pick new articles for you to read based on your profile. Although being served a steady diet of information that matches your interests may sound like a good idea, it means you never get to consider other perspectives and might therefore end up with rather one-dimensional views on a particular topic.

Governments also collect data, with China already having implemented widespread camera surveillance and facial recognition and the EU introducing digital passports and digital coronavirus certificates.

The good

Despite their disadvantages and risks, algorithms can also be extremely beneficial. Without algorithms or data, many problems and challenges would lead to major disasters. There are countless examples, but I will only highlight a few.

Firstly, algorithms can help improve how we treat diseases. Algorithms already play a crucial role in the treatment of many diseases, such as the radiation therapy used to fight cancer. Internal radiation therapy (also known as brachytherapy or curietherapy) involves inserting needles and introducing radioactive material into the body through them. Algorithms enable us to determine how many needles to insert, as well as the optimal insertion sites and depth, in order to target as many cancer cells as possible and spare healthy cells. In other words, algorithms can help to save lives.

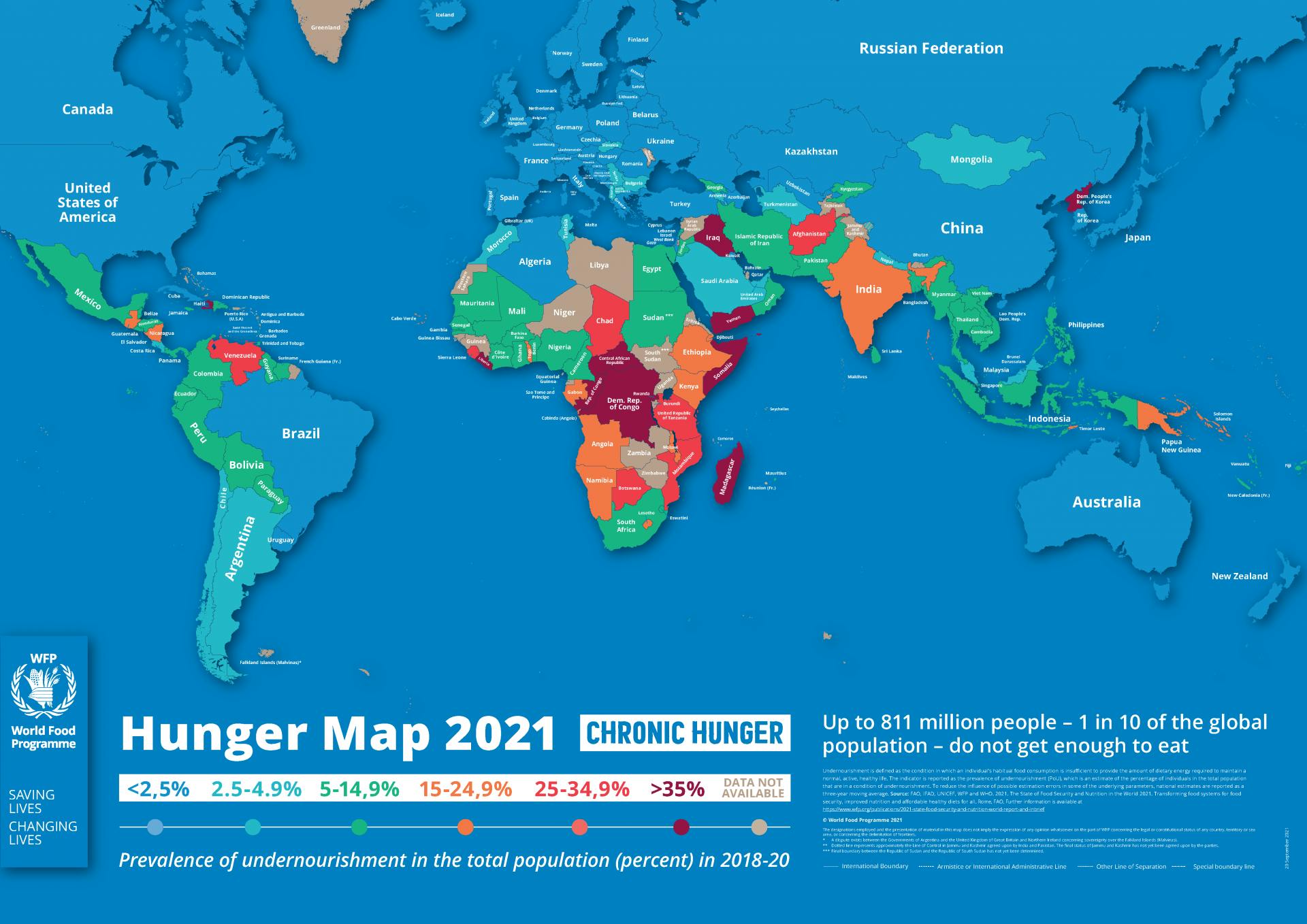

Secondly, algorithms will help us achieve the United Nations' sustainability goals. In 2015, the United Nations set 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for 2030. SDG 2 aims to achieve zero hunger in the world by 2030. The World Food Programme plays a key role in providing food for refugees, using algorithms to optimize the efficiency of their logistics. They’ve even also incorporated nutritional requirements in the algorithm to optimize menus. It saves The World Food Programme USD 150 million every year, which can subsequently be used to feed another two million refugees.

Holy Grail of fairness

Algorithms are more widely used than ever before and affect people and organizations alike on an ever greater scale. People should be treated fairly no matter what their situation, which is why it is so important to make algorithms fairer. Despite all our efforts, however, algorithms will never be perfectly fair. There is no Holy Grail of fairness, and what we perceive as “fair” changes over time. Choices are often subjective, but algorithms can make them more objective.

Fortunately, public interest in the fairness and objectivity of these algorithms is gradually increasing, thanks to pressure from lawmakers and regulators, the media, and society. It is worth considering whether it is even possible to look at “the other” unburdened by prejudice and bias. By definition, algorithms are based on rules and assumptions, which always involves including and excluding certain aspects and factors. But even if you include these aspects in your algorithms, the data can still lead to undesirable outcomes. Algorithms cannot be good or bad, but how they’re applied certainly can be.

“There is no Holy Grail of fairness, and what we perceive as ‘fair’ changes over time. Choices are often subjective, but algorithms can make them more objective.”

Download your magazine

This article is part of the 4th issue of our magazine Data and AI in the Boardroom. Get your copy now.

We've asked leading figures in different sectors about how their organizations plan for the predictable and prepare for the unpredictable, and how using data and analytics in innovative ways help them to deal with uncertainty.

Don't miss out on the next insights

Sign up to our mailing list and be the first to receive our newest insights and digital magazine in your mailbox on a quarterly basis.

About Goos Kant

From a farmer's son who helped his dad calculate which cows to keep, to logistics optimization expert and Managing Partner at ORTEC: Goos Kant has been committed to making an impact since a very young age. Kant specializes in logistic planning and prefers to combine academia with a more practical, applied approach. Kant calls academia his “home away from home”, and he has been a professor of logistics optimization since 2005. He’s the project leader of a major R&D project on horizontal collaboration, is regularly an invited speaker at conferences and lectures for executive education programs. Optimizing mathematical models is in his nature, but he is also driven to scout out improvements that cannot be found in models.